Published on: Apr 7, 2023

Introduction

“If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants” said Sir Isaac Newton in 1675. What do these shoulders look like? In modern science, these take the form of scientific papers. But why do we trust them so much? What is so special about a scientific paper, compared to for example, a newspaper article? On the surface, scientific papers might look like some generic “.pdf” files you find on the web. Sure, they are full of nice graphs, fancy words, and scientific-looking equations. They are written by scientists, who are supposed to be experts in their fields. But looking fancy does not mean being correct, and scientists make mistakes (as a scientist myself, I would say I make lots of mistakes in fact). So clearly, there has to be a better reason to trust these papers. In this blog, we want to take you on the journey of publishing a scientific paper, to show you that it is much more than what it looks like.

The research

Any good scientific paper starts in the lab. Here, researchers develop new technologies and theories that they put to the test with simulations and experiments. In the mmWave communication field, for example, this could mean spending weeks measuring propagation channels. Then the algorithm is run in software, perhaps multiple times with different variations, emulating the measured channel. In other cases, it even involves spending months or years building a whole system from scratch. In this phase, the scientists are faced with the first trap of the process: confirmation bias. Humans, which scientists are a subset of, tend to only look for evidence of what they believe is true, and dismiss the evidence against it. This means that the average human would rarely realize that their beliefs are false. Thus, scientists need to make a constant and conscious effort to use the tools at their disposal to check if their theses are correct, not that it is. In fact, the major part of checking if your theory is correct is trying to prove it is wrong! This critical thinking is a major component of scientific research and, as we will see, continues beyond the lab.

Writing

After the results have been thoroughly checked, it is time to write. This is notoriously known as the least fun part of a researcher’s job, but nevertheless, an important one. While writing a scientific paper, there are a few things to keep in mind, first and foremost, the reproducibility of results. This means that the paper should contain all of the information about the experiment you conducted, such that another scientist could repeat the experiment independently and, ideally, obtain the exact same results. The lack of this characteristic makes the results impossible to verify and therefore impossible to trust. This also brings us to the next requirement: motivation of the claims. In science, the idea of believing something is correct just because an authority in the field said so is utterly unacceptable, and every piece of information that is provided needs to be based on a solid ground. Clearly, it is impossible to fully motivate and prove each and every sentence in an article of a few pages, so here is where our giant’s shoulders come back, in the form of references. If you look at a scientific paper in fact, you will find lots of numbers between brackets within the text, and a list of other scientific papers at the end. What do these mean? As the reader might have guessed, they are the supporting arguments behind the claims of the author. So, for example, if I claim that MINTS is one of the most promising projects on 5G/6G [42], I do not need to fully explain why this is true in the text. You can just check the list at the end of the document; at number 42 you will find a full scientific paper that proves what I claimed. And no, 42 is not a large number of references; scientific papers can sometimes have even more than 100 references.

Peer review

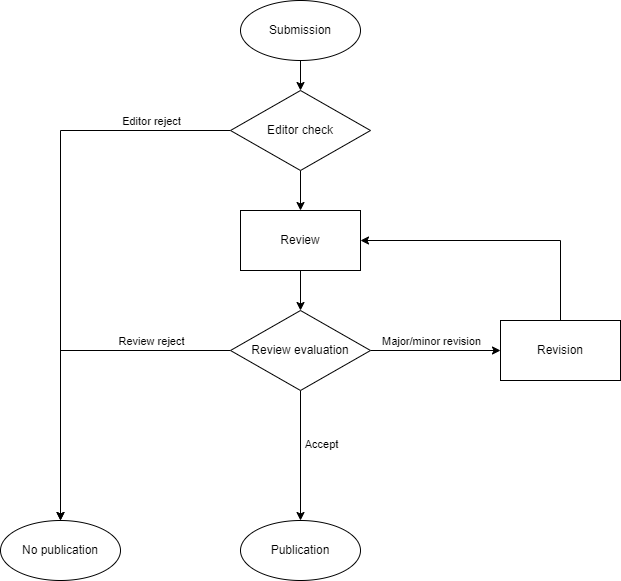

Now that our paper is complete, we just save it in “.pdf” format and upload it to the web, right? Well … not so fast. To publish a scientific paper, it needs to undergo a process called peer review. The process, also described in Figure 1, starts by submitting the work to a journal or conference. An editor then checks the paper to make sure it is in the correct format and within the length limits of the publisher. If the format is correct, the main part of the process can begin.

The paper is sent to multiple scientists working in the same field, typically 3 or 4, who read the paper and check if the technical content is correct. After their evaluations, they report to the editor and provide a list of comments. The process is anonymized, so the authors and reviewers do not know each other. Moreover, the publishers usually check for conflicts of interest. For example, I cannot be asked to review a work from my colleague that co-authored one of my papers last year. This guarantees that the process is fair and impartial.

After the result of the reviews is received by the editor, a few different things can happen:

- The paper gets accepted and is published as is. This is by far the least common thing that happens after the first submission, and is worthy of throwing a party if it ever does!

- You are required to perform a minor revision. This means that some details are incorrect or not fully explained, and you need to clarify those details before the paper can be published. Minor revisions are in general characterized by the fact that the changes you need to make do not impact the final conclusions of the study. Of course, when you do a revision, the paper is reviewed again after the changes.

- You are required to perform a major revision. This means that you have probably messed up something. This happens when the reviewers find major inconsistencies in your results and often require you to go back to the lab and redo some experiments.

- Your paper gets rejected. This can happen for a variety of reasons: the quality of the work is not deemed good enough by the reviewer, the topic of your study does not fit the theme of the journal or the same results have been published by somebody else several months/years before.

Note that revisions do not guarantee that the paper will be published after the changes, so for a single paper you can get multiple rounds of revisions. In such cases, the peer review process can last for a very long time, and some papers take over a year from the first submission to their publication.

Figure 1: Peer review process

Conclusion

As we explained in this blog, publishing a scientific paper is a lengthy and complicated process. So, now let us ask ourselves the initial question again: Should we trust scientific papers? I believe the answer should be clear now: The research is done with critical thinking, trying to avoid the traps of confirmation bias, the writing is rigorous and detailed, and each claim is proven and motivated. Finally, several other scientists try to find flaws and mistakes in your research, making sure that any issues are addressed before publication. All of these factors differentiate scientific papers from any other kind of publication, making them more trustworthy and relevant for someone seeking information.

If you were able to stick until the end and can’t wait for more content and you also want to know about us and our projects, you can always follow our social media channels.

References

[1] https://twitter.com/mintsnetwork

[2] https://www.facebook.com/MINTSETN

[3] https://www.linkedin.com/company/mints-etn

…

[42] A. Bedin, “Obvious things don’t need proof”, 2023

…

[127] https://b5g-mints.eu/